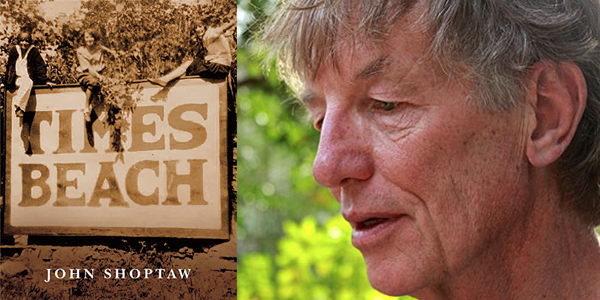

John Shoptaw wins 2016 Northern California Book Award; discusses winning book, Times Beach

This academic year has proven itself to be an exciting one for Professor John Shoptaw; after publishing his book of poetry Times Beach in late 2015, he received both the Notre Dame Book Review Prize, as well as the 2016 Northern California Book Award for Poetry for his work.

Earlier last month, English Alum (’13) and current English PhD student at Stanford University Armen Davoudian, sat down to discuss the book with Professor Shoptaw, which you’ll find below.

Armen Davoudian: Times Beach follows the course, through geography, and the plot, through history, of the Mississippi River. It opens with poems of beginning – among them a sequence on baptism, an ode to a well-spring playfully titled “Oh Well,” and an elaborate originary (mock-)epic centered on the river’s headwaters in Lake Itasca – and it ends in Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta, where the river empties into the Gulf of Mexico, with “The Dead Zone.” Or so would run a linear account of the book and of the river; yet as you write, “a river is not a line … but a whole floodplain of possibilities: the course it currently takes / along with all those it might have.” Is this also an account of poetry? How are the poems in Times Beach not linear narratives but, in a metaphor Charles Olson would have recognized, plains or fields of possibilities?

John Shoptaw: “I dwell in Possibility –” as Dickinson put it, “A fairer House than Prose –” The Mississippi is mighty, powerful and full of possibility. So yes, possibility means poetry. And a poetry book, to paraphrase Rimbaud, would be a deliberate derangement of all of its poems. I fiddled with the ordering of the poems in Times Beach. I originally placed “Itasca” first and “The Dead Zone” last. Then I reminded myself that I was only writing about the river system because I was born and raised in the floodplains of the Missouri and Mississippi, most particularly along Little River in New Madrid county, the epicenter of the 1812 earthquake (the largest ever recorded in the continental U.S.). So I thought of starting with my baptism in the ditch that drained our hardwood swamp for logging, and radiating outward. The final ordering of poems (each new section let me begin again) keeps something of both trajectories. T.S. Eliot wrote that “What might have been” remains “a perpetual possibility” only “in a world of speculation,” but that’s where poems like to dwell. I am taken with John Ashbery’s idea of a perpetually latent happiness, which includes for me the possibility of a latent sadness, a darker house or storm shelter than prose.

AD: History and the environment emerge as perhaps the book’s most ambitious topics. More meticulously researched, footnoted, and detailed than is usual for a collection of poetry, Times Beach is an astonishing feat of historiography and nature writing – of what used to be called natural history. One may even say, twisting a metaphor from Marianne Moore, that the poems here try to put real toads in real gardens, vigorously blurring the line between description and imagination. You even invoke the 19th century panorama, a documentary genre if there ever was one. Why this degree of … realism?

JS: Possibility rooted in actualities – that’s my tree house. Neither the New York School nor Language Poetry, two huge influences on me, showed much interest early on in either the historical or natural world. I wanted to write a muddy impure poetry dependent on the life – biographical, historical, and natural facts – beyond the margins of the book. So I reconsidered Heaney (through Muldoon), Williams, and Moore. At the same time, I didn’t want to merely versify cultural or environmental history; they’re clearer in prose. So no naked realism for me, no matter without manner. Take the opening natural event in “Blues Haiku”: “I want to blur” from the shore like a crawfish, and then sit “pinching moss off a cypress knee,” standoffish like a self-possessed Poet. And when I wrote “I might just walk barefoot” into the Mississippi “like a Sadhu to the Ganges,” I was thinking of baptism and also the immense river festival, the Kumbh Mela, where the river isn’t a symbol but a revivifying medium. Without that far-fetched likeness, my foot-washing (metrically speaking) wouldn’t be poetry.

AD: Times Beach tells not just a factual but also a literary history. What is the book’s relationship to the poetry of the past? Your subject matter, allusive range and formal models span an incredibly vast terrain, from Homer and the Bible to the obscure Modernist American poet William Alexander Percy. Long-form poetry, in particular, is frequently invoked: the Redcrosse Knight of Spenser’s Faerie Queene, the “stringent meter” of Longfellow’s national epic and 19th century bestseller Hiawatha, the quatrains and marginalia of Hart Crane’s The Bridge, T. S. Eliot’s philosophical meditations on time and memory in Four Quartets. Does this book, secretly and not so secretly, harbor epic aims? Why were you drawn to long forms such as the poetic sequence of “Wahite” and the (as far as I know) sui generis triple sestina of “Shuffle”? What did, to take another instance, the dramatic form of “Heebie Jeebies: A Dream Masque” – reminiscent as much of Miltonic masque as of James Joyce’s dream-drama in the “Circe” chapter of Ulysses – allow you to do that cannot be done in the (conventionally) brief lyric poem? Despite these European literary siblings, is there something uniquely American about this bigness, about the attempt to disprove the allegation, as one poem puts it, that “America has no Art commensurate with its Size”?

JS: It’s true, I like to rummage (and play) around in literary history. How could I resist writing my Mardi Gras poem “Heebie Jeebies” as a Miltonic masque, given that the first-ever Mardi Gras Krewe was named Comus? What better form for “Shuffle” than a triple sestina, which shuffles its end-words like cards, or for a poem featuring the courtly Percy, “knight” of the Mississippi Delta Red Cross, than Spenserian stanzas? I should add that John Ashbery (the subject of my dissertation and first book) used the Hiawatha hemistichs in “At North Farm” and a (mathematically impossible) double sestina in Flow Chart. One thing I like about these strange poetic forms is that they let me take up uncongenial perspectives: environmental ruination; Ojibwe removal; evacuation and dynamiting; sharecropper peonage.

And yet you’re also right that the elephantine form in the room is the epic, surely the interstate highway not taken of Times Beach. The first temptation in making a poem out of the Mississippi is bigness. John Banvard succumbed by making a three-mile-long panorama of the river, big if not great (none of it survives); “Banvard’s Panorama” became my cautionary self-parody (self-parodies are apotropaic). Why not an epic? Or a three-mile Reznikoff newsreel? I wanted to sidestep the bardic adventurer, the encapsulating narrative, and the pretension of objectivity. So yes, I was attracted to the mixed modes of Melville and Joyce which I thought would let me have it both ways, lyric and epic, and let me fluctuate with the topic. You can walk into the same river twice and then you can’t.

AD: This book of poems calls itself Times Beach in defiance of an act of historical erasure:

Times Beach,

the place name, proved indelible

only initially; once the EPA

added its whitewashing agents, the name started

fading from highway signs, directories,

guide books, maps.

These lines describe an institutionalized effort by the EPA and the state of Missouri to erase the dioxin contaminated Times Beach, a town once home to more than two thousand people, from public memory. Times Beach, then, attempts to be a missing memorial, a witness to an erased place. Several other poems, too, mount a sustained critique of capitalism by recording the humanly and naturally detrimental consequences of the cotton, corn, and international banking. Could these poems be considered in the lineage of what Carolyn Forsché has called “the poetry of witness,” poetry that records, condemns, or otherwise bears the mark of (often political) injustice?

JS: I admire the poetry of Forché and also of Czeslaw Milosz, both of whom practiced a poetics of witness. But I mostly wasn’t there, and even when I was I didn’t know it, so why should I pretend my readers are? The book begins “I want to blur. . .” That said, I called on many old and new friends up and down the river to testify. Many of the poems are indeed charged with a rhetorical undercurrent, and might be called ecojustice poems. “Times Beach,” for instance, links the spraying of waste oil on the town’s dirt roads with Vietnam because the sludge came from a Missouri chemical plant where Agent Orange was manufactured. What if the white latecomers to my Missouri swampland had built among the giant trees they found there instead of clearing them and sharecropping among their stumps? I strove not to be lyrically anthropocentric; the bottoms are not a meditative backdrop but a reason for beings being what they are. At the same time, we humans, the one species who can willfully destroy their environments, have a special responsibility to preserve and tend kindly what we have left. What can ecopoets do? Change the way people think and feel about and respond to the life and land around them.

AD: Times Beach is, inevitably, a printed and paper-bound book, but it’s also a full-on rebellion against the necessarily silent and still medium of print. The first poem carries the musical title of “Blues Haiku,” and the (fictional) drama of “Heebie Jeebies” recalls the eponymous Louis Armstrong song from the 20s. Do you see your poetry as aspiring to the condition of music and song? At the same time, this is a textually and paratextually complex book, with marginalia, epigraphs, endnotes, distinctive fonts and intricate spacings and lineation that are reproducible only in a written and not oral or heard medium. How do you negotiate this tension between poetry’s textual and aural ambitions? Do you imagine, when you write, an audience of readers and hearers?

JS: Yes, I did want the poems in Times Beach to be song and dance, tunefully patterned and audibly rhythmic. I scored my poems on the page, I like to perform them, and I hope readers will be tempted to drawl a blues haiku or two. And you’re right that Times Beach is a celebratory performance of oral culture, those muddy bubbles, undertows, and eddies of language around the willow islands of literacy. I grew up and worked among people who were unlettered, neither literary nor very literate. Neither of my parents graduated from high school. You couldn’t buy a book, a newspaper, or a record in my town. I remember the glee with which my schoolmates chanted “aint aint a word cause aint aint in the dictionary!” The thrill came not just from misbehaving, but from a sense that mainstream culture didn’t hear their countercurrents.

But I never joined in. I was too intent on educating myself, correcting my “pronounciation” as we said it, on masking my accent and cracking the books, hoping thereby to escape the poverty swamp of the Missouri floodplain. I remember how stunned, and also excited, I was when I heard the Missourian T.S. Eliot reading The Waste Land. I was determined to follow his lead. The overriding metaphor of Times Beach is that the education of the tongue is writ large in the engineering of the river. Do I contradict myself? Very well then. So I think of Times Beach as a hybrid of oral and written, performed and printed culture. “Blues Haiku” grafts the syllabic haiku onto the accentual Mississippi Delta blues tercet; “Ghastly Dew” grafts a Homeric ecphrasis onto a chatty biography. Much of the vibrancy of recent U.S. poetry comes from a mixing of media and a mashing up of tongues and styles. May Times Beach flourish in that oral-literate world.

AD: Speaking of literacy, of education . . . what about UC Berkeley? California comes up only once in Times Beach, and then only by way of happenstance, as the aleatory “Shuffle” finds a “coincidence” between the earthquakes of New Madrid and the tremor-prone Bay Area. How else do the facts of living, writing and teaching in Berkeley reverberate in the poems in this book?

JS: Teaching at a public university, like the one in Missouri where I was taught, has been a gift and an opportunity. Many of my first-generation college students are surprised and heartened to learn that I too began at a community college, and worked my way through to graduation. Times Beach kept me thinking about where I’m from and how I ended up where I am. It’s a curious fact that I wrote my Mississippi river book almost entirely in California. Before moving out here, I educated myself by going east, to New England and New York. For many years I had no feel for West Coast, or trans-Pacific poetry. I didn’t really appreciate Gary Snyder or Kay Ryan, couldn’t make out Robert Duncan or Jack Spicer, and hadn’t even heard of Simon Ortiz or Joy Harjo. When I moved to the East Bay, I found the climate equally inscrutable. Every morning looked like rain and every afternoon felt like a cold front. We bought a house with (to me) a large garden and learned how to tend it. And I found myself flourishing in an ecological cultural climate. The poet and colleague here who has made all the difference to Times Beach and to me as a poet has been Robert Hass. Through his poetry, prose, and his environmental teaching and practice, Hass shook up a number of my presumptions about a poet’s place and part in the cultured natural world. What began as a poetry of place evolved into an ecological poetry. It may not be too much to say that, while the Mississippi is my topic, its rendering is Californian.

You can also watch Professor Shoptaw reading a selection poems from Times Beach at last year’s Lunch Poems event.

There’s just no escaping dat ole man river!

A lot here to chew over and think through.