A Way of Reaching Back: Mai Der Vang (’03) on the poetry of Afterland

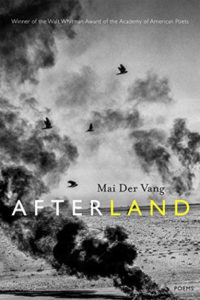

In 2017, UC Berkeley English alumna Mai Der Vang (’03) published her first book of poetry, Afterland, which recounts the Hmong exodus from Laos after U.S. forces abandoned their Secret War, and subsequent refugee experiences of Hmong exiles and their descendants in the United States. The book was selected by Carolyn Forché as the winner of the 2016 Walt Whitman Award from the Academy of American Poets, was longlisted for the National Book Award, and has received major media coverage. Recently, graduate student Evan Klavon interviewed Vang about her development as a writer, her time at Cal, and the relations between her poetry, history and ancestors, and contemporary communities and culture.

—interview by Evan Klavon

Evan Klavon: I’d like to begin with a couple biographical questions before we talk specifically about Afterland. You were an English major at UC Berkeley. Were you already interested in poetry and writing before going to Berkeley? How did your interests develop while there? Are the poems in Afterland influenced by your studies during that time?

Evan Klavon: I’d like to begin with a couple biographical questions before we talk specifically about Afterland. You were an English major at UC Berkeley. Were you already interested in poetry and writing before going to Berkeley? How did your interests develop while there? Are the poems in Afterland influenced by your studies during that time?

Mai Der Vang: My interest in poetry began during my early adolescent years. While I was an avid reader as a tween, I also wrote friendship and love poems that were entirely corny and clumsy. In high school, I was fortunate to have amazing English teachers who rejuvenated my interest in poetry. And then finally, when I arrived to Berkeley and decided to study English, I began to consider poetry more seriously as a craft from having had the chance to take classes with literary powerhouses such as Robert Hass, Lyn Hejinian, and others. It was such an important return to poetry for me as my interest and appreciation for it began to deepen. On the other hand, looking back on the poems I attempted at this time in my life, I am pretty sure they will never see the light of day. None of the poems in Afterland are directly influenced by these early poems. During my undergraduate studies, however, I was heavily mired by questions of my Hmong history and sense of cultural belonging, which I think on a thematic level are important to the book.

EK: Place and relationships with place are central to your book, and landscape imagery is prevalent throughout the poems. You grew up in Fresno, in the San Joaquin Valley of central California, and then moved to Berkeley, and I know you’ve also studied in New York City. I’ve also lived in all three of those places, and I’m curious how their different physical and cultural landscapes may have affected the way you think and write about place.

MDV: You’re right, many of the poems incorporate a variety of landscape imagery and some of them draw upon the San Joaquin Valley in particular along with other natural environments. When I was working on these poems, the landscapes served as an entry point not only into writing and thinking about the biodiverse world or habitat of that poem but also into crafting the language to embody that habitat, however imaginative it could be. Beyond the locations you indicated, the other key geographical terrain is that of Laos, the country of my parents, one that I have not had the fortune to visit and one that I am only able to imagine, at the moment, through my parents’ renderings.

EK: Let’s turn now to your book. Its title, Afterland, seems to me a good place to begin. The “land” half can be taken as referring to the ancestral homeland of the Hmong people in Laos, and also to the United States as the home of Hmong refugees who fled Laos after the US abandoned the secret war there in 1975. The “after” can be related to the position of exile after the war. And yet, while your writing is “after” that history, the past is not dead and buried in your poems—it continues to have a haunting afterlife. Are there other ways the book’s title plays upon these complexities? How do you think about the relations between history and poetry?

MDV: Having been born right around the time that my parents resettled in this country, it’s clear to me that I exist in the “after” of this war and that is all I have to grasp at. And yet even as the war has passed, it remains ever-present in the Hmong collective memory. I think that’s why for this book, I was deeply immersed within the notion of the “after” or a “post-” state of being. In this way, the title speaks to the idea of geographies or spaces we inhabit after a crisis, landscapes where the body ends up after it has experienced something severe. For me, the act of poetry is a kind of history-telling, it’s a way of making sense of these states of the before and the after, of exerting language toward longevity.

EK: The book clearly extends beyond your personal experiences. In “Gathering the Last of the Dark,” you write “Storage in my / mind is not my own but those // who save before me. … I have gone this long / only to discover there are / veins living outside the body.” What was your process like in transforming research and the experiences of other people into your own poems?

MDV: In this particular case, and in the case of many of the poems in the collection, I was actually gesturing toward my ancestors, who although are not me in the literal sense, are still clearly part of me, who I am, what I’m made of, where I come from. The poems are a way of reaching back to them. But in the case of infusing research and other experiences into poems, I think it’s important for a poet to ask questions such as what does the research say and whose experiences do these belong to and what relationship does the poet have to both. Is the poet part of that experience or is the poet an outsider looking in? As a Hmong person who inherited this war and whose parents and elders still suffer the effects of it to this day, I felt collectively part of these experiences on familial and historical levels even if I did not see the war firsthand.

EK: Along with the evident topics of geographical, cultural, and linguistic displacements, there’s a thread of spiritual displacement that runs through the book. These displacements are shared by the refugee generations and their children—and yet, those born in diaspora would seem to be doubly displaced. This dynamic, of difference amid continuity, seems to me to be central to how poems relate to each other within the book. How did your sense of the themes and relationships develop as you wrote and revised?

MDV: To inherit this history of displacement as someone who did not directly experience the war but did however grow up during the difficult resettlement years as a result of the war was very heavy. The war loomed as this abstract thing to me as a child and so I felt displaced in my inability to understand it. My parents could not fully explain or tell about it. The spiritual displacement is central to the book as well. So many spirits left behind, abandoned, stranded in that war without a proper ritual to transition them into the next life or the next landscape. I often think about those displaced spirits as being focal to that geography.

EK: Your poetic imagery is consistently striking. There are directly stated descriptions, some of which are shocking: “your son’s head in the rice / pounder, shell-crumbled.” Then there are metaphorical transformations that remind me of magical realism, a kind of displaced vision: “The crowded dead / turn into the earth’s / unfolded bed sheet.” And then there is a surrealist mode that seems to express emotion more than represent a scene or event: “Alley sharks invade / The window of my ribs.” How do these different modes of imagery fit into your interests or goals in writing the poems?

MDV: Aesthetically, I’m drawn to imagery that can shape-shift and embody diverse forms while pushing against an expected realism. I’m aware that my imagery can be jarring and unsettling but I’m okay with that. Growing up, thinking about and imagining this unimaginable war and living in the aftermath of something that came before me, nothing seemed to ever make sense to me. For example, I didn’t understand why my parents were refugees and how we ended up here, or why my grandmother would talk about people that were left behind. I think that’s why I’m drawn to imagery that is so far-fetched that in its inability to be realistic, a kind of quasi truth-telling or truth-depiction begins to emerge, if that makes any sense.

EK: I was also struck by the variety of apparent speakers and addressees that appear in Afterland. There are the poems that are titled as if letters—“Dear Soldier of the Secret War,” “Dear Exile,” and “Dear Shaman”; poems that take up the “we” of a group and even the voice of the land (“I the Body of Laos and All My UXOs”); and then other poems where “I” and “you” appear to refer to specific figures, though their identities and relationships are typically left open-ended. The style does not change to imitate some other persona, but rather it feels like you are displacing yourself into another viewpoint, or perhaps channeling another voice. To what degree were these choices intentional or intuitive? How do these dynamics fit into the work of your writing?

MDV: I was intentional in thinking about the voices and perspectives from which to construct the poems. For me, figuring out which perspective to write from, whether first person, second, third, none, etc. served as one of the important entry points into crafting the poems. In revising the poems, I also changed some of them from first to second or vice versa, and switched the perspectives around in order to allow a more nuanced voice to surface. It was about trying to find balance between what compelled, who was telling it, and to whom. Sometimes the speaker would address a person or a subject. Other times, the speaker was simply addressing the self. Personifying the landscape and speaking through it also felt natural to me, having grown up in a family that practiced shamanism, animism, and the belief that everything on the land has a spirit.

EK: I’d like to ask about how you think about the various audiences of your work. What is your sense of the relations between poetry and community? Has this been affected by the community work you’ve done in Fresno and by your editorial work with the Hmong American Writers’ Circle? Do you think poetry can be of value in contemporary American culture? In what ways?

MDV: I’m grateful that my work is finding all kinds of audiences, from those who have never heard of the word “Hmong” to those in the Hmong community who are beginning to learn more about and seek out poetry, literature, and publishing. It’s been incredibly encouraging to witness how a book like this has helped spur dialogue and interest on both sides. The act of writing and publishing poetry is relatively new to my community, so I’m also grateful to groups like the Hmong American Writers’ Circle who advocate for it at the grassroots level, and in doing so, are helping to build and strengthen new audiences of readers and writers. Poetry has always had value, but I believe its value has deepened even more so in this era and particularly in a country where people are hurting inside from political, social, and racial turmoil. Through poetry, there is both consolation and truth.

EK: Finally, for readers of this interview interested in learning more about Hmong history or reading more Hmong-American creative writing, would you recommend a few further books or writers?

MDV: Absolutely! I encourage readers to check out two anthologies: How Do I Begin? A Hmong American Literary Anthology and Bamboo Among the Oaks. There is also a small yet growing group of Hmong literary writers who have published books: Burlee Vang, Pos Moua, Soul Vang, May “Hauntie” Yang, Khaty Xiong, Mai Neng Moua, and Kao Kalia Yang, to name a few. I’m hopeful that in the years ahead, this list will continue to grow!