This is Not a Writing Blog Post

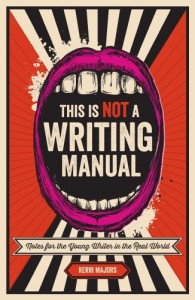

Kerri Majors (’98) is the author of This is Not a Writing Manual: Notes for the Young Writer in the Real World, which came out on July 9 from Writer’s Digest. Publishers Weekly called TINAWM “Candid, honest advice and reflection from a writer who’s been there,” and Kirkus described TINAWM as “An upbeat and honest guide for teens already considering writing careers.” Majors is also the founder and editor of YARN, an award-winning literary journal of YA writing, and her short fiction and essays have been featured in publications across the United States. She earned her MFA from Columbia and now lives in Massachusetts with her husband and daughter. She is working on a novel.

We had the chance to catch up with Majors recently about her new book. The conversation ended up meandering across a number of different topics, including the current boom in college writing and MFA programs, why writers should buy planners, and Majors’s own writerly biography. It contains a lot of advice for young writers, and plenty to interest writers and readers of all ages.

Let’s start with a little bit of background about your writing career. When did you first know you were interested in writing? How did that interest develop as you got older? How have you grown or changed as a writer over the course of your career?

Well, my new book is about that very long journey. I got interested in writing my own stuff in grammar school. I started writing my first novel, on a yellow legal pad, in fifth grade. I circulated chapters of my second unfinished novel among my friends in seventh grade. In some ways, I’m still the same: I still write regularly, and find it incredibly satisfying to share my work (okay, yeah, there is an ego-stroking aspect, but just as much, I’ve been open to feedback and I’ve always wanted to improve my writing).

One of the main ways I’ve grown and changed is that I’ve learned to dream smaller. For many years, I dreamed BIG—Oprah, NYT bestseller list, all that stuff that’s already gone to Jonathan Safran Foer and Suzanne Collins. But I’ve learned through a lot of writerly hard knocks, that I’m probably not that kind of writer. And that’s okay.

In addition to your career as an author, you are obviously heavily invested in developing and supporting young, talented writers (both through YARN and in your new book). What led you to “write about writing”? Perhaps more importantly, why is the “young adult” audience a good demographic to address yourself towards? What hurdles do you see young writers facing these days, from simply sitting down to write to actually getting published (a subject that forms the final section of your new book)?

It’s funny, because I NEVER imagined I would write a book like this. For a long time, I didn’t even read books like this. But then in my late twenties, I read Anne Lamott’s wonderful Bird by Bird, and all that changed, because I suddenly felt understood…and inspired.

The YA audience—and by this I mean actual young adults, aged 14-24, though older writers can certainly read and enjoy my book!—needed a book about writing and the writing life that was speaking directly to them. Bird by Bird, Steven King’s On Writing, and many others, are excellent, but they don’t address the particular needs and concerns of a writer just starting out: a writer who is worried about making money and supporting their writing, for instance.

Making money—that’s certainly a big hurdle facing young writers. How do you do that, and still nurture your creative writing? Or, as one of my Berkeley professors once put it, how do you not “kill your creative writing”? It’s a simple question with a complex set of answers that I try to address in the book, alongside other important issues like jealousy, rejection, and plain old how to get the job done.

Your new book has a chapter on “The Creative Writing Major.” How do you feel about the proliferation of creative writing instruction, particularly for undergraduates? What are these majors doing that could be good for young writers, and what are they doing that could actually be counter-productive?

Huge question. I can’t really do it justice here—but you’ve given me a great blog idea! In brief: I worry about the proliferation of creative writing majors, because (as I discuss at greater length in my book) I worry about writers narrowing their scope down to writing too early in their education. College is the one and only time you have the freedom to immerse yourself in subjects you love. I was an English major (lit, not writing) with an Art History minor, and the synergy between those two subjects REALLY inspired me and my creative writing. Plus I learned so much about the world by studying them together. If I had to make one suggestion to undergraduate creative writing programs here, I’d say: Require your students to double-major, or to minor in something other than literature.

Your new book begins with a chapter entitled “Drafting: Buy A Planner” that talks about how writing emerges from steady, organized effort (you use the Tortoise and the Hare as an analogy). Later in the first section, you have a chapter called “Come At It From The Side” that essentially encourages thinking outside the box while writing—allowing yourself to surprise yourself, you might say. I really like the idea that this kind of startling improvisation (coming at writing from the side) arises from a practice (writing itself) that depends on rigorous planning and coordination. Do you see managing this subtle tension between organization and surprise as one of the more difficult things to master as a young writer? What makes it easier? What does it feel like or look like to achieve the correct balance?

Your summary and extrapolation are beautiful! Yes, this is a hard tension for ANY writer—young AND old. Gosh, I’m not sure anything makes it easier. What makes it more doable is doing it. Over and over again. You read interviews with even the most established writers, and they say that every novel, every new project, is still daunting. It’s like learning to write all over again. But that’s so cool, isn’t it? It never gets boring. Writers are the original life-long learners.

You clearly subscribe to the “it takes a village” mantra when it comes to writing, with chapters like “Publishing Writing Is A Team Effort” and “Bosom Writing Buddies.” One of the less appealing (or more appealing, depending on your perspective) things about writing is that it can be very lonely. Why is overcoming that—by writing with, for, or to someone—important for young writers?

Young writers are often drawn to writing because it’s work they can do by themselves. I think writers are often the kids who wind up doing all the work in group assignments in school….or who don’t do any of the work for the group, because they get fed up with the group! Though I must say that in the YA community, there are A LOT of genuine team players, which is why I love it so much.

Partly, overcoming the natural writer’s tendency to be alone is critical for a mercenary reason: without Twitter, and other kinds of social media, your career is going nowhere. It’s incredibly hard for writers to live monkish lives these days. You have to find and cultivate your audience, because that’s what readers expect.

On a more touchy-feely level, it’s also just nice for writers to feel part of a community of people who suffer the same slings and arrows, but also drink the same champagne. Other writers are your tribe, if I may use too many metaphors to answer your question.

Can you also connect this back to the question regarding writing programs: do these programs foster appropriate relations among young writers? I would love to hear you muse briefly on the difference between, but also perhaps the inextricability of, networking and friendship as a writer.

Yes, writing programs (formal and informal) absolutely foster important relationships between writers. And that inextricability…. Let me give you an example that I hope shows what you mean:

YARN won a very cool award from the National Book Foundation a few years ago, and as a result, I got to go to all the National Book Awards celebrations—the 5 Under 35, the official reading, and the big awards gala. I was able to enjoy that incredible privilege because of my editorial relationships with the writers I published who made YARN great.

Then, at the after-party, I met an agent who hooked me up with some of his writers. We published one, Diana Renn, who turned out to live one town over from me in my own new locale, so we met for coffee one morning. We became friends. We swapped pages of our novels in progress, gave each other feedback, and I even invited her to become the Fiction Editor of YARN—and she’s doing an awesome job.

So writing relationships lead to more writing relationships. Some of them will be career-making, others will be life-saving. Some will be the best cup of coffee you’ve ever had, and that’s essential, too.

Let’s end with a very simple question. If you could give one piece of advice to writers just starting out, what would it be?

Take small steps, and celebrate small victories. Getting into a workshop is a big deal! Getting a compliment on a story from a stranger is a big deal! Your first “personal” rejection from a journal or agent is a big deal! Don’t be disappointed if the bigger dreams take a loooooong time to come true. The writing life is not all about fame and fortune and affirmation on a grand scale; it’s about living your life in celebration of words—your own, and those of others.

Posted by Jeffrey Blevins

1 Response