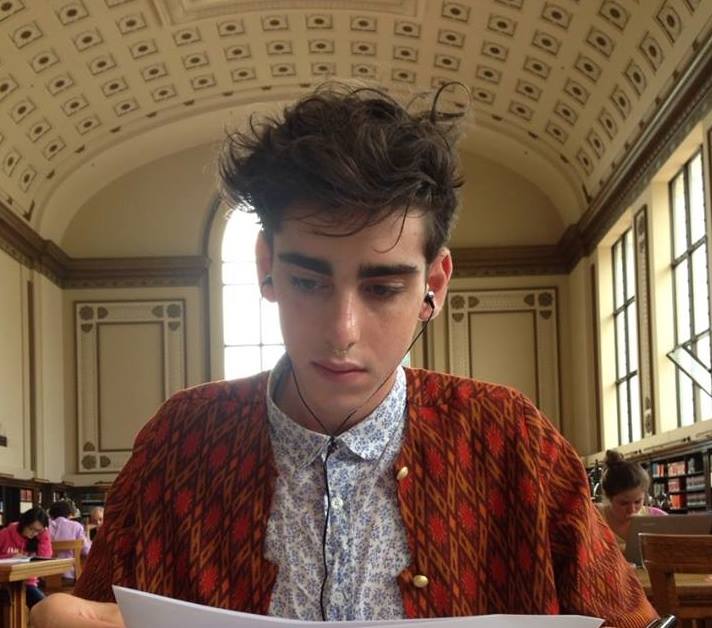

David Adam Getman (1992-2014): In Memoriam

A selection from David Getman’s thesis, edited by Namwali Serpell, has just been published at the journal Post45.

David Adam Getman, a brilliant writer, artist, son, brother, and friend, died in a traffic accident in the early morning hours of August 25th, 2014. David, who was a 2010 graduate of the Milken Community Schools in Los Angeles, is survived by his three sisters and his parents.

When he passed away, David had just graduated with Honors from the Berkeley English department. He was a stellar student and made a deep impression on everyone with whom he worked: undergraduate peers, graduate student instructors, and professors alike. As a long time resident of co-ops here at Cal, David’s delightful presence as a friend and neighbor will sorely be missed. His creative and scholarly art was elegant and strikingly original. He was charming and gentle, yet intensely astute. The word that keeps coming back to us when we talk about David is “luminous.” His radiance in our lives went beyond his remarkable mind.

This website gathers some of David’s work and some memorials–in the form of poetry, prose, illustration, and video–from his teachers and friends at Berkeley. Many of these efforts were collaborative. David strongly believed in deep connection and communal creativity. David was a loyal, engaged, and gifted member of the Berkeley community. We mourn his loss and celebrate the brief, incandescent light of his life.

His website can be viewed here.

Personal tributes to David:

Ivonne Arias (a short tribute)

Chrystia Cabral (a poem)

Heather Do (recipes)

Keko Jackson (a photograph)

David Marno (a selection of David’s writing)

Holly Sanderson (a poem)

Lara Sarkissian (a video)

Namwali Serpell (on David’s writing)

Claire Stringer (poems and drawings)

Esther Yu (a short tribute)

The following are excerpts from David’s Senior Honors Thesis, “Daft Punks” (2014).

On Pillows: Kathy’s listening becomes performance when she begins to “slowly dance,” eyes closed, “singing along softly each time those lines came around again,” calling a warm embrace into existence (71). She transforms the object of address, ‘baby,’ into a baby-ish mode of relation, a purer appreciation of sound and touch over sight and language. The song blueprints a ritualized space, one of her “little private nooks createdout of thin air” (74). Childhood and maturity are no longer diametrically opposed as she holds a pillow to “stand in for the baby”: “I was doing this slow dance, my eyes closed, singing along softly” (71). Kathy’s is a dance of companion species; she (quite literally) rehearses “the dance linking kin and kind.” A pillow-baby is a paradigmatic object of desire in Never Let Me Go: a textural, inanimate object, a substitute for a child of the heterosexual imperative that nevertheless hints at queer temporality and phenomenology. The pillow—as opposed to say, a doll—foregrounds the conspicuous absence of the child. But if we honor the pillow as a legitimate love object and not the absence of one, we forge new terms of ‘proper’ affiliation. The quasi-private nature of the fantasy registers the cruelty of capitalism: how can we create sensuous recesses from overly condensed time, out of thin air? For Kathy, this involves misreading a song and an object in an expanding niche for feeling.

…

The couple form continues in [Felix] Gonzalez-Torres’s work, going public in another “Untitled” series. I refer to giant photographs of the artist’s unmade bed that were pasted onto billboards around New York City in the early-1990s.

The bed is empty. The sheets are ruffled, but a pristine white. Two pillows register the impression of heads that at one time lay there. The medium of the billboard, scattered across the city, scrambles the signification of the piece. Is a creative ad exec or a risqué artist asking us to consider bed, bath, and the beyond? The viewer imagines a scene. The lovers (?) have evacuated the bed. Let’s say the sun has risen. Were there any disclosures the night before? Is there any closure in the morning? The lovers might be a few steps away, sipping morning coffee – or just one, all alone, it become his mourning coffee. Perhaps the two are no longer of this world. Perhaps the sex was bad, memorable for every texture except that of the partner’s skin. The billboards tower over neighborhoods in all boroughs, immersed in contexts that are all quite distinct, but across that diversity the question remains the same: how to feel enlivened and embodied in one’s encounter with an impersonal object, with “that stuff.”

On Mourning: The call to animate reaches a fever pitch in “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)—a memorial for Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s partner Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS-related illness in 1991, the same year the piece was made. According to the Art Institute of Chicago:

The installation is composed of 175 pounds of candy, corresponding to Ross’s ideal body weight. Viewers are encouraged to take a piece of candy, and the diminishing amount parallels Ross’s weight loss and suffering prior to his death. Gonzalez-Torres stipulated that the pile should be continuously replenished, thus metaphorically granting perpetual life.

I remember my first encounter with this “portrait” of Ross. It emerges from the corner of a gallery like a glittering spider web. Solemn art-lovers and candy-starved toddlers together break museum etiquette. The collective unwrapping process is noisy. Once you’ve taken the candy from its shell, there isn’t much to do but take it in your mouth. It melts on your tongue as a rush of sugar mingles with the sublime dread of symbolically ingesting a dead lover. One final thought, always: what do I do with the plastic wrapper?

The portrait of Ross breathes. It rises and falls with its interlocutors. The piece proposes a queer vision of health, interpellating viewers into collective responsibility for a body. That is, Ross’s immune system (or, at the very least, its allegory) is no longer a wholly personal, hermetic, self-regulating entity; rather, it is given shape by the threats to it, i.e., a community of consumers who enact the work through its ingestion. The shift is significant. As Mel Chen writes, the “internalization, even privatization, of immunity helps to explain the particular indignation that toxicity invokes, since it is understood as an unnaturally external force that violates (rather than informs) an integral and bounded self.” It wouldn’t take much for Reagan-era homophobes to twist this reasoning – seeing those with compromised immune systems as themselves the toxic threat. To an extent, our participation in “Portrait of Ross” implicates us in dying and grieving. “Portrait of Ross” contests the bodily integrity of its namesake, suggesting that in L.A., in life as in almost-death, Ross is always in flux. Yet Ross lives again, not only in L.A., but wherever the work is displayed, in the sensual absorption of his allegory. His immune system and candied body become a sensual and textural stimulant. Engaging the portrait is a distinctly bittersweet moment, as we are brought into an abject eroticism with Gonzalez-Torres’s lover.

Consider the piece today, and its meanings shift. Safety has come to mean something different, to have taken on another “form.” To swallow the candy we remove its prophylactic wrapper, evoking changing perceptions of safe sex practice in an era of increasingly risk-based health and bio-political management. We might consider whether innovations like Truvada (a pill up to 99% effective in preventing HIV transmission) allow for closer contact, or whether it might have been precisely the rough textures of the condom (awkward conversations, torn wrappers, and latex limits) that brought us closest to intimacy.

I think the most profound meanings lay in the museum guards who stand sentry over“Portrait of Ross,” enacting a paradoxical kind of stewardship over the work. Museum guards are often assumed to be outside the circuits of artistic value and meaning; here, however, they are responsible for protecting an artwork that museum visitors have just as much responsibility to ingest and make their own, which raises fundamental questions about the very nature of culture. In Never Let Me Go, the teachers of Hailsham are called “guardians.” The euphemism productively misrecognizes acculturation as guardianship, but there are meanings to the term that are worthy of our consideration. The etymology of “guarding” is in “caring” and the roots of “care” are in grief and sorrow. So we can appreciate “culture” in the sense of acquiring it, but we can also appreciate it as a process of caring and grieving. With regards to the work of Gonzalez-Torres, we strive to have an encounter with these objects less out of a desire to tap their pristine aura (to feel their cultural value); rather, we strive knowing that in appreciating them we can grieve safely, knowing that our deficiencies will be restored. We know that overnight someone will fulfill their role as steward. We know that, come tomorrow, there will be more candy.