The Poem at the End of the Mind

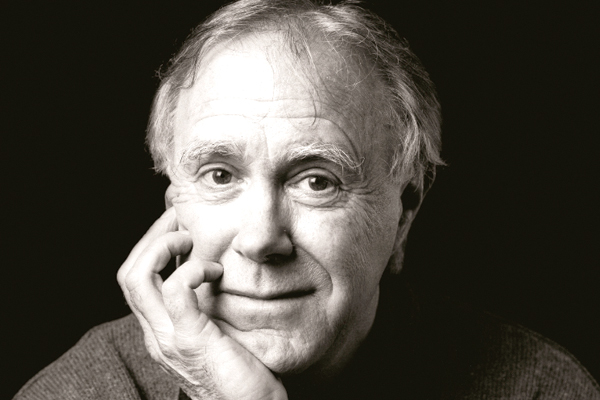

In 2014, Robert Hass won the Wallace Stevens Award, the highest honor given by the Academy of American Poets. Below is John Shoptaw’s piece on the occasion of Hass’s award. A shorter version of this piece was featured in the department’s newsletter in December 2014.

“Among the modern poets,” Robert Hass told me once, “I believe Wallace Stevens thought the most deeply about our relation to the natural world.” I would have expected him to name Frost or Moore or Jeffers. But for Hass—who received the 2014 Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets—Stevens is key because he didn’t presume that he knew the world. In conversation with the biologist E. O. Wilson (The Poetic Species, 2014), Hass remarked that Stevens “thought the world was basically unknowable,” offering evidence from “Of Mere Being”:

A gold-feathered bird

Sings in the palm, without human meaning,

Without human feeling, a foreign song.

The contrastive “human” tells us that Stevens’s bird is no Cartesian or Yeatsian automaton of “hammered gold and gold enamelling,” but an unimaginable subjectivity whose song harbors its own “meaning” and “feeling.” “Every species lives in its own sensory world,” Hass recalled Wilson saying, a statement he incorporated into “A Note on ‘Iowa City: Early April.’” There the poet and a raccoon eye each other, the poet speculating, “He might have been studying an enemy, / he might simply have been curious, / but I don’t know” (Sun Under Wood, 1998).

For Hass, the consequences of our not knowing are immense. No longer solitary selves surveying a soulless natural world, humans may once again “move among great powers and mysteries and only glimpse their meanings.” Knowing something only partly or provisionally engenders in us an insatiable desire to know it more intimately. This desire is the burden of Hass’s “Envy of Other People’s Poems” (Time and Materials, 2007):

In one version of the legend the sirens couldn’t sing.

It was only a sailor’s story that they could.

So Odysseus, lashed to the mast, was harrowed

By a music that he didn’t hear—plungings of sea,

Wind-sheer, the off-shore hunger of the birds—

And the mute women gathering kelp for garden mulch,

Seeing him strain against the cordage, seeing

The awful longing in his eyes, are changed forever

On their rocky waste of island by their imagination

Of his imagination of the song they didn’t sing.

One poem distinctly enviable here is Stevens’s “The Idea of Order at Key West”: “plungings of sea” echoes Stevens’s “meaningless plungings of water” while “rocky waste” registers the titular “Key West.” (“Idea” has long reverberated in Hass’s ear. He began “Palo Alto: The Marshes” (Field Guide, 1972) with “She dreamed along the beaches of this coast,” noticing only days later, as he recollected, the echo of Stevens’s “She sang beyond the genius of the sea.”) But in “Envy,” Hass recasts the parts. In “Idea,” the poet and his friend (“we”) witness a woman (“she”) walking and singing by the sea, while in “Envy,” Odysseus (“he”) and the sirens (“they”), like the poet and raccoon in “Note,” gaze at and imagine each other—a satisfyingly contemporary mutual obsession (mirrored in “Seeing . . . seeing”), itself perhaps prompted by another Stevens poem, “The World as Meditation” (“She [Penelope] has composed, so long, a self with which to welcome him, / Companion to his self for her, which she imagined”).

But Hass’s most striking re-imagination is surely the “mute” sirens. What are we to make of sirens who don’t sing? Well, though “she” sings in “Idea,” we don’t catch so much as a word of her song, and what we don’t know we must imagine. Hass told Wilson that Stevens “seemed to think that humans learn everything about order and beauty from the natural world without ever really knowing what it is.” So too, Hass’s Odysseus imagines a music in the unfathomable coastal sounds and locates its spirit in the muted sirens (perhaps merely drowned out by sea, gulls, and wind). Which is where Hass’s parabolic title comes in. We can imagine the isolated kelp gatherers, awestruck by Odysseus’s famished gaze, suddenly seeing themselves as longed for. But what can poets or poems see in each other? Speaking about the way “art creates desire,” Hass asks whether there is “anyone who hasn’t come out of a movie or a play or a concert [or the beach at Key West] filled with an unnameable hunger?” Sublime works in particular “open up something raw in us, wonder or terror or longing.” Readers of a terrific poem thus occupy both positions, “longing” to know more and more and “changed forever” by each harrowing encounter. What must it be like to have dreamed up “Idea” or “Envy”? We can only imagine.