Jeffrey Knapp Featured at the Townsend Book Chat

The Townsend Book Chat this week will feature Professor Jeffrey Knapp speaking about his new book, Pleasing Everyone: Mass Entertainment in Renaissance London and Golden-Age Hollywood, on Wednesday, September 27th, in the Geballe Room, 220 Stephens Hall, from noon to 1 p.m.

In Pleasing Everyone, Jeffrey Knapp opens our eyes to the uncanny resemblance between Renaissance drama and the incontrovertibly mass medium of Golden-Age Hollywood cinema. Through fascinating explorations of such famous plays as Hamlet, The Roaring Girl, and The Alchemist, and such celebrated films as Citizen Kane, The Jazz Singer, and City Lights, Knapp challenges some of our most basic assumptions about the relationship between art and mass audiences. Above all, Knapp encourages us to resist the prejudice that mass entertainment necessarily simplifies and cheapens whatever it touches. As Knapp shows, it was instead the ceaseless pressure to please everyone that helped generate the astonishing richness and complexity of Renaissance drama as well as of Hollywood film.

What follows is an excerpt from this work.

4

One Step Ahead of My Shadow

Never relax. If you relax, the audience relaxes.

– James Cagney

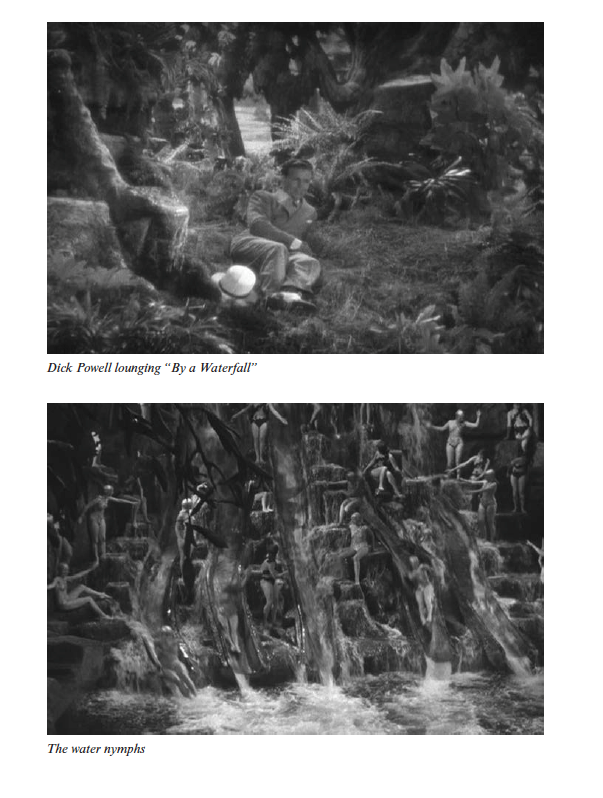

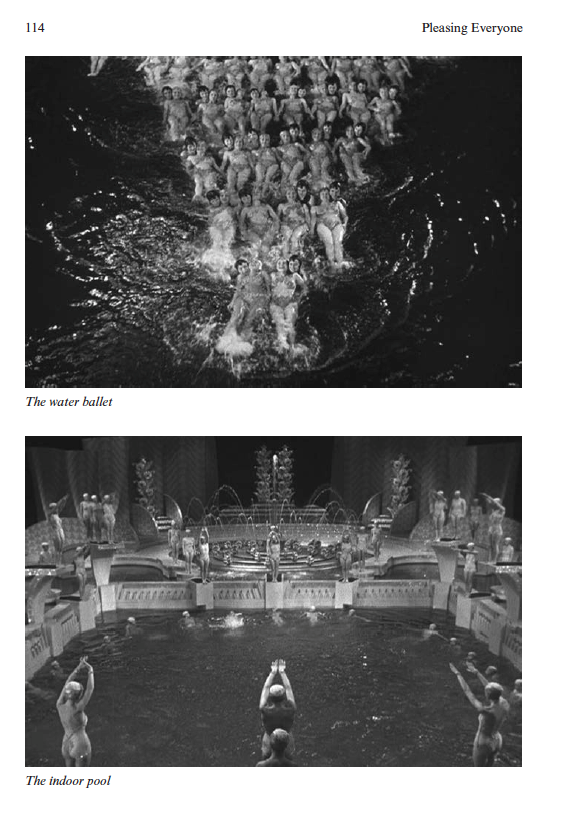

Movies, it was said throughout the twenties and thirties, meant escape for “the drudging millions,” a release from “the chain of monotony” that bound them to “the same piece of work all day long and all the year long.” But where did these toiling masses escape to? In Warner Bros.’s 1933 musical Footlight Parade, at the start of a Busby Berkeley extravaganza that has been called “perhaps the finest musical production number ever conceived and executed,” the audience is invited to unwind “By a Waterfall,” where a languorous Dick Powell croons of being able to “drift and dream” as he enjoys “love in a natural setting.” Once Powell falls asleep in the arms of Ruby Keeler, however, the action picks up considerably. First, several water nymphs appear and beckon Keeler to their forest pool, where they are joined by an ever-increasing number of other nymphs in an elaborate water ballet, until the camera pulls back to reveal that their synchronized swimming is now taking place in a grand indoor pool. After more water shows there, the nymphs reappear on a six-tiered hydraulic fountain and arrange themselves into further stunning displays before a final transition through water brings us back to the sleeping Powell. It’s all a strange excursion from Powell’s own getaway. “I appreciate the simple things,” his character begins the number singing, but then, as contemporary reviewers pointed out, we go on to witness a series of complexly choreographed “mass-maneuvers,” executed with a “drilling and precision” that clearly “reflect a prodigious amount of preparation.” “It took us over a week to shoot that number,” Berkeley himself stressed to the New York Times in 1933, “and the girls were in the water most of the time. The pressbook for the film likewise advertised the round-the-clock toil that went into building the “Waterfall” set:

“Twenty-four hours a day workmen labored, sometimes as many as two hundred at a time.” In the film itself, the “Waterfall” number is anything but a break from work: it’s rather the culmination of a backstage plot that has dramatized the grueling process of putting on musical shows. What kind of holiday from labor makes a spectacle of labor to the laborer on holiday?