Forgotten Chapters of Department History: #1 Ella Young’s Lectureship

by Kamila Kaminska-Palarczyk

The first woman to hold an endowed lectureship in the English Department was a celebrity. She entered the department through the Celtic Studies program, the first degree-granting program of its kind in the country, created in 1911. Two decades later the program appointed Irish writer Ella Young as the Phelan Memorial Lecturer in Celtic Mythology and Literature.

The first woman to hold an endowed lectureship in the English Department was a celebrity. She entered the department through the Celtic Studies program, the first degree-granting program of its kind in the country, created in 1911. Two decades later the program appointed Irish writer Ella Young as the Phelan Memorial Lecturer in Celtic Mythology and Literature.

Young had graduated with a Master’s Degree from the Royal College of Dublin, Ireland, where she studied political science and law; however, she quickly became invested in literary pursuits. Although today she is better known for her authorship of children’s literature and poetry, as well as her early championing of environment preservation, her ardent cultivation of an “authentic” Irishness was the trait that stood out for her contemporaries. Especially inspired by her witness of and participation in the 1916 Uprising (during which she is alleged to have hidden ammunition in the floorboards of her home for the Irish Republican Army), Young thought it essential that the revitalization of Irish culture be nourished through Celtic mythological roots. And she insisted that those myths expressed a more direct and intimate connection to the natural world than the cultures of modern industrial societies offer.

Her political activism and passion for Celtic lore, though, caused problems for her entry into the United States even as they made her an instant celebrity. When an especially intrusive immigration officer discovered her literal belief in fairies, Young’s mental fitness to enter the county became questionable; it was suspected that she might become a “public charge.” While Young was thus detained at Ellis Island, newspaper headlines published dramatic runners, including “Irish Poetess and Uncle Sam to Fight It Out.” Despite the charge that she was mentally unstable and therefore posed a threat, “librarians and writers over the country appealed to the State Department” (“US Delays Entry for Irish Poetess”) on her behalf, and argued that the University of California needed her intellectual labor. It was under these conditions that Young took up her endowed lectureship at Berkeley and began creating her legacy as an eccentrically captivating teacher.

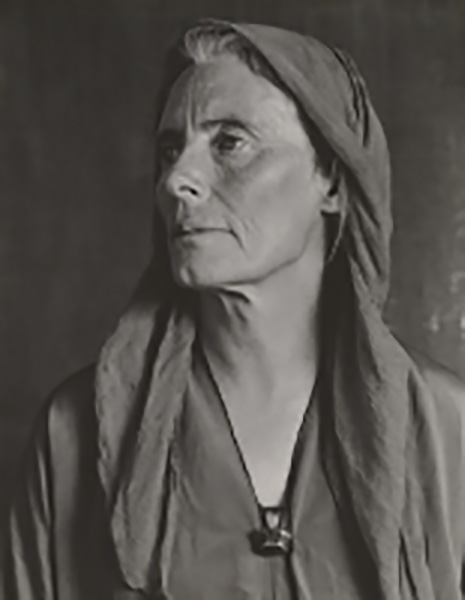

Dorothea McDowell’s biography, Ella Young and Her World, describes Young as “living two lives, the first 60 years in Ireland and the final 30 in California.” She theorizes that Young, once at Berkeley, attempted to reconcile her physical distance from Ireland through the creation of an ultra-Irish persona, which was especially dependent on costume and public performance. Her public lectures proved memorable not only for what she said but also for how she presented herself: she wore what she thought of as the traditional Celtic robes of a Druid bard, which she called her “reciting robes,” to visually portray an authentic Irish identity. While lecturing from her new home on the Pacific Coast, enrobed in typically dark purple, Young was determined not to regress into “dead knowledge.” To avoid the threat of monotony, she never wrote her lectures down, explaining, “They are born between myself and the audience” (McDowell, 585). In Wheeler Hall, Young delivered public lectures on topics that ranged from “Halloween Among the Celts” to “Dublin Wit” and “The Art of Storytelling and Craftsmanship in Poetry.” These lectures’ titles are intriguing, yet audience members (including mathematician Derrick Lehmer) more vividly recalled her presentations on the faery world: “Whether one listener, a roomful, or a crowded hall, she held all spellbound” (McDowell, 586). Part of her appeal was her insistence that the supernatural world portrayed in Celtic folklore and literature could bring her listeners into a closer relationship with the natural world around them.

Young was admired at Berkeley, and in turn she admired the town, especially its exotic flora, breathtaking views, and youthful exuberance: “Berkeley is a town that one should see in the springtime,” she wrote in her memoir. “Street after street has been planted with the Japanese plum tree, with the Japanese cherry, with almond trees and the japonica which is called fire-bush. Its hills are very green. Cloud shadows lie on the bay. And the town itself is full of young people: girls and boys; orange-coloured sweaters, rose-red skirts, shoes that tap gently on the pavement” (McDowell, 585).

Outside of the university, and most likely after her retirement, Young named herself “Airmid,” after the ancient Irish Celtic Goddess of healing. But her devotion to the Celtic revival extended beyond her fabricated persona; it was also deeply embedded in her writings. A majority of her works, both during her time in Ireland and after her immigration to California, were adaptations of Celtic lore. Her extensive list of poetic works and children’s stories includes Celtic Wonder Tales (1910), The Wonder-Smith and His Son (1927), and The Unicorn with Silver Shoes (1932). Young’s The Tangle-Coated Horse (1929) even received a Newbery Honor, recognizing the story’s “significant contribution to American children’s literature.” When scholars and editors—including John Matthews and Denise Sallee—began to compile a collection of Young’s works, they observed that the diegetic worlds of her literature accepted “the presence of such beings as ogres, magicians, and strange beasts … [as] a perfectly natural state of affairs”(Matthews and Sallee, 17). Young’s success in reconciling generations of tradition through her literature of the magical realm is especially resonant when “she puts contemporary language into the mouths of strange beasts alongside the ‘high speech’ of epic” (Matthews and Sallee, 17).

Although the surface of Young’s prose creates a magical realm for children, librarian and lecturer on children’s literature Frances Clarke Sayers argues that “to read the books of Ella Young … is to move in a world of epic proportion, heroic deed, and heroic character” (Matthews and Sallee, 8). In an interview, Young explained her fascination with the thin veil between the natural and fantastical realms: “It’s fairy lore that makes the world beautiful … there are fairies all about us, if we’ll only look for them. How sad it is that a materialistic world laughs at them and their beauty … The fairy kingdom is a vast realm of magic where most anything can happen” (Matthews and Sallee, 9). When questioned about the intended audience of her children’s literature, Young simply responded, “Since people always like what is not intended for them, perhaps a few grown-ups will read it also” (Matthews and Sallee, 17). Young’s remark suggests that any person can connect to the fantastical in literature and think beyond the purely materialistic gratifications of the commercial world when inspired by nature and ancient myths. She advocated “the natural world and our relationship to it” as an alternative to consumerism and was quoted in the LA Times (1926) as “deploring the practice of supplying quantities of toys to American children … [because] it inhibits the development of the imagination.”

Her unconventional ideas, however, were also subject to critical scrutiny. Young’s work was frequently denigrated through American conceptions of the Irish Renaissance. American literary critics often portrayed her male counterparts as the truly creative elements in the Irish Literary revival, casting the women as mere popularizers: “Only a Yeats could turn this material into great poetry, but the women gathered it into books, so that everyone could read the ancient lore and be warmed and heartened by it” (Scurge). Skeptical attitudes toward Irish sovereignty and assumptions of the country’s general inferiority also clouded Young’s reception: “Ireland’s closest present-day link with the fairies, is coming to America. Not, perhaps, one of the major lights in the Irish literary Renaissance, [Young] is nevertheless an important figure, breathing … interior Gaelic life” (Jewell). An especially unforgiving American critic, Thomas Scurge, argued that “the weaknesses of [Young’s] method [reflected] in a way the weakness of the Irish literary movement as a whole.” This was the same critic who believed that the “Irish Renaissance [was only] the brief and brilliant sunset of European romanticism” (Scurge).

Thus despite Young’s scholarly success in Gaelic translation and adaptation, she still confronted an intersection of oppressions as a woman within the academic and literary worlds. Cast as merely a minor figure in the Irish literary scene because of her desire to restore Celtic beliefs and link them to the preservation of nature, Young was positioned as an impractical eccentric who “spread so romantic a background for the modern Irish State,” which was only “slowly establishing itself as a political unit” (Jewell).

Young, however, actively challenged this narrative from her new home in California in several ways. In addition to making herself the American ambassador for literary Ireland through her public lectures, she also cultivated the local California creative establishment. She was a frequent guest at the home of the prolific and influential poet Robinson Jeffers, who was also influenced by the Celtic revival. Jeffers and Young joined forces in comparing what they saw as the physical and spiritual similarities between California’s central coast (especially Big Sur) and Ireland’s western coastal regions. Young was also a close friend of Virginia and Ansel Adams, the renowned photographer of California’s wilderness, who made Yosemite Valley a symbol of the state. Ansel Adams took several portraits of Young in her “reciting robes”. Circulating in the networks of recognized California artists and conservationists, Young was no longer just a minor remnant of the Irish Celtic revival; she became a unique hybrid Irish-Californian and decided to spend the rest of her life on the Central Coast.

Young thus created a new land of mythic enchantment in California, and she eventually seems to have decided that it was superior to the one she left behind. Drawing on Young’s 1945 autobiography, entitled Flowering Dusk: Things Remembered Accurately and Inaccurately, historian Kevin Starr sums up her mature view, “There were sea spirits at Point Lobos, she claimed, and fairies, although not as many fairies as there were in Ireland—yet stronger fairies, stronger spirits on Point Lobos and the Big Sur to the south than in Ireland” (Starr 325). In a gesture indicative of both her lifelong devotion to natural preservation and her dual Irish-Californian identity, Young left the copyright for Celtic Wonder Tales and Other Stories to the “Save the Redwoods League” (McDowell 545).

Sources

“An Authority on Celtic Mythology: Fairies Are Realities In Her World.” Los Angeles Times, 3 Apr. 1926, p. 18. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

“Irish Poetess and Uncle Sam to Fight It Out.” Chicago Daily Tribune, 5 Apr. 1931, p. 25. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Jewell, Edward Alden. “Elfland Send An Ambassadress to US.” New York Times, 18 Oct. 1925, p. SM12. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Matthews, John and Denise Sallee, editors. At the Gates of Dawn: A Collection of Writings by Ella Young. Skylight Press, 2011.

McDowell, Dorothea. Ella Young and Her World: Celtic Mythology, The Irish Revival, and the Californian Avant-Garde. Academica Press, 2015.

Scurge, Thomas. “Irish Literary Notes.” New York Times, 12 Aug. 1945, p. BR13. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Starr, Kevin. Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963. Oxford UP, 2009.

“US Delays Entry for Irish Poetess: Ella Young Might Become Public Charge, It Is Explained.” Washington Post, 5 Apr. 1931, p. M3. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.