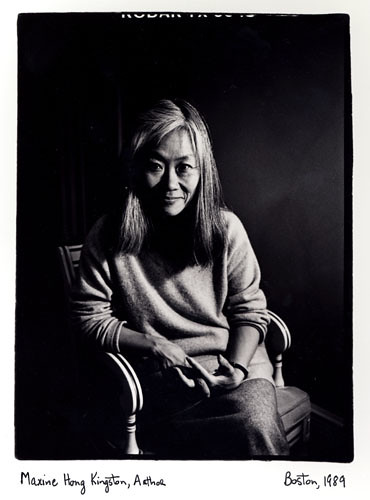

Maxine Hong Kingston: The Spearhead of Asian American Studies and Literature

By Lucia Salazar

Maxine Hong Kingston, the critically acclaimed author of The Woman Warrior (1976), China Men (1980), and Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book (1989), graduated from UC Berkeley with an English degree in 1962 and returned as an English department faculty member in 1990. Her work has garnered a number of high-profile awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Book Award, and the most prestigious prize awarded to artists by the U.S government, the National Medal of Arts. Kingston’s work is acclaimed for both its literary merit and its foundational place in two related fields: Asian American literature and Asian American Studies. The Woman Warrior was the first commercially successful novel by an Asian American woman featuring a Chinese American woman protagonist.

Maxine Hong Kingston, the critically acclaimed author of The Woman Warrior (1976), China Men (1980), and Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book (1989), graduated from UC Berkeley with an English degree in 1962 and returned as an English department faculty member in 1990. Her work has garnered a number of high-profile awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Book Award, and the most prestigious prize awarded to artists by the U.S government, the National Medal of Arts. Kingston’s work is acclaimed for both its literary merit and its foundational place in two related fields: Asian American literature and Asian American Studies. The Woman Warrior was the first commercially successful novel by an Asian American woman featuring a Chinese American woman protagonist.

Because Kingston was one of the first widely-read Asian American authors, her work was often imagined to depict “typical” experiences of the immigrant community. Before more authors diversified the field, Woman Warrior was included on course syllabi as a token of the entire culture. Thus, although the initial reception was enthusiastic, Kingston was dismayed by its often misguided, if not blatantly racist, reception. Just one example of this counterproductive acclaim is the Peninsula Herald’s review: “[The Woman Warrior] brings to mind ancient rituals, exotic teas, superstitions, silks, and fire-breathing dragons” (quoted in Kingston 1982). In 1982, Kingston admonished the critics who superimposed exotic stereotypes on her novel by noting that “they praised the wrong things”: “The critics who said the book was good because it was, or was not, like the oriental fantasy in their heads might as well have said how weak it was, since it in fact did not break through that fantasy” (Kingston 1982). Today the critical stereotyping by American book reviewers serves to remind us of just how new the phenomenon of the Asian American literary work was at the time. Reviewers to whom literature written by and about Asian Americans was unfamiliar tended to reach for the clichés closest at hand. And Kingston’s push-back publicly identified her as an outspoken protector of Asian American literature against the pitfalls of exotification.

A different sort of critique was also launched at the book from inside the Chinese American community, targeting departures from the historical Chinese story in The Woman Warrior. The playwright Frank Chin, also a UC Berkeley English Department alum, is perhaps the most well-known, and most severe, critic of Kingston’s work. He accused it of pandering to white Christian readers by altering traditional Chinese myths to make them more palatable to non-Chinese readers, thus boosting the book’s popular appeal (Iwata 1990). In response, Kingston explained that she aimed to embody the historical oral tradition of Chinese folk tales, which naturally changes with each retelling: “From the very beginning, every time a story is being told, it changes in order to fit the circumstances and needs of people who hear it” (Zagni 2006). In her book China Men, Kingston tells and retells the story of her father’s immigration from China four times, striving not so much for historical accuracy as for layers of possible meaning.

Nearly fifty years after The Woman Warrior was first published, Kingston’s work has withstood the challenges from both outside and inside the Chinese American community to achieve canonical status in American and Asian American Literature courses. The longevity and breadth of her appeal are striking. “I think Maxine Hong Kingston won the debate [with the critics] through the sheer lasting power of her book,” said Professor Colleen Lye of the Berkeley English Department. “People recognized the artfulness of the book. The more there was publishing on the subject,” Lye continues, “the more it ceased to be the sole representative.” And the more Kingston’s literary experimentation and achievement are recognized, the less her works are expected to adhere to strict historical accuracy.

A large part of her accomplishment was her successful blending of the personal memoir genre with fiction. At the outset, publishers and scholars categorized Kingston’s work as nonfiction, a designation that downplayed its literary nature. Kingston’s publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, insisted on labeling The Woman Warrior as autobiography in order to make it more marketable to American audiences. While the book is certainly about Kingston and her mother, it bends the genre by narrating invented as well as remembered events, personal history and mythic adventures, character development through quotidian reality and through imaginatively inhabiting other existences, sometimes even supernatural ones. In a 2006 interview with the French Magazine Revue Française d’Etudes Américaines, Kingston spoke about the pattern of mislabeling stories written by and about immigrants and minorities as nonfiction and the effect it has of ostracizing them from the realm of literature. The blend of genres, though, has also made Kingston’s work a staple of both Asian American interdisciplinary studies and literature. She commented on the silver-lining of being mislabeled a writer of nonfiction: “My work is in anthropology classes, in sociology, history and ethnic studies classes, but it’s also in literature classes… it seems that I have broken categories” (Zagne 2006).

Kingston has indeed “broken categories” in a number of ways, including by repositioning common tropes of Chinese Literature. Professor Lye points to the characters Kingston focuses on as an example of this subversion, “She was the first to write an ethnic autobiography in the Asian American tradition that centered on mothers and daughters rather than fathers and daughters or fathers and sons, which were the main examples of Asian American autobiography in a fictionalized and non-fictionalized form.” Lye explains that Amy Tan later chose to write about the relationship between mother and daughter in her national bestseller The Joy Luck Club. This rejection of the patriarchal form and centralization of an immigrant woman as representative of the American woman was received as an intersectional feminist work.

Kingston is a trailblazing woman writer who has constantly had to cope with criticism, misreading, and the mislabeling of her work. The deciding factor in all of the controversies surrounding her work has been Kingston’s undeniable literary power and originality, which has stood the test of time. In The Woman Warrior, she draws a clear lineage between her mother’s “talk-story” (the oral relation of the stories of from China) and her own writing. She filled in the details of her mother’s stories imaginatively as a way of both realizing a collective identity and finding an individual one as a writer. English was not a popular major for Chinese Americans at the time. Indeed, Kingston came to Berkeley from Stockton with the intention of studying Engineering; but, as she later told an interviewer after winning the National Medal of Arts, “It felt like I was in prison.” She thirsted for imaginative freedom and found it in the English Department: “It was fun. All we did was read and talk about reading” (Knudsen 1997).

She has definitely taken inspiration from the school and the setting of the Bay Area; the novel Tripmaster Monkey’s protagonist is a graduate of UC Berkeley living in San Francisco during the psychedelic 60s. Moreover, her work and career seem to express some of UC Berkeley’s best qualities: resilience, subversion, and inventiveness. The now 79-year-old Kingston plans to release her last novel after she dies, and she is inventing a form for the posthumous work. In March she told The New Yorker, “I know I can die at any moment. So, I was writing a work that could end at any moment” (Hsu 2020).

Work Cited

Hsu, Hua. “Maxine Hong Kingston’s Genre-Defying Life and Work.” The New Yorker, 1 June

2020,www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/08/maxine-hong-kingstons-genre-defyin

Iwata, Edward. “Is It a Clash over Writing…” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 24 June

1990, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-06-24-vw-1117-story.html.

Kingston M.H. “Cultural Mis-readings by American Reviewers.” In: Amirthanayagam G. (eds)

Asian and Western Writers in Dialogue. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1882,

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-04940-0_5

Knudsen, Jenn D. “Maxine Hong Kingston: She Celebrates Being a Human.” Inside Oakland,

UC Berkeley, 1997, projects.journalism.berkeley.edu/oakland/culture/maxine.html.

Zagni, Nicoleta Alexoae. “An Interview with Maxine Hong Kingston”, Revue française d’études

américaines, vol. 110, no. 4, 2006, pp. 97-106.

www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-d-etudes-americaines-2006-4-page-97.htm#