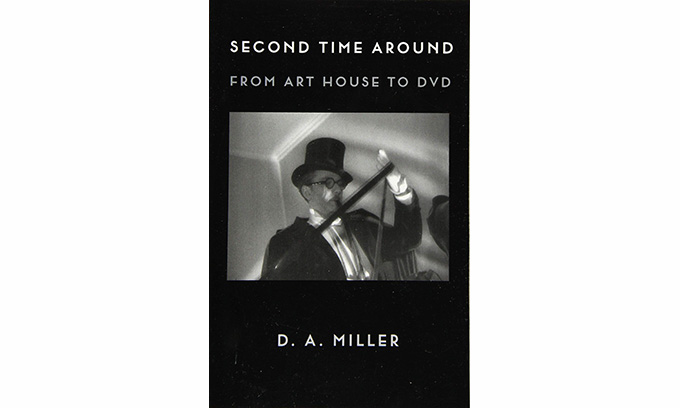

D.A. Miller’s Second Time Around: From Art House to DVD

In Second Time Around: From Art House to DVD (Columbia University Press, 2021), Professor D.A. Miller watches digitally restored films by directors from Mizoguchi to Pasolini and from Hitchcock to Honda, looking to find not only what he saw in them as a young man, but also what he was then kept from seeing by quick camerawork, normal projection speed, missing frames, or simple censorship. In this excerpt, he recalls from his childhood the first time he saw a movie twice.

The first second time. Until I turned fifteen, and could go downtown on my own, I had almost no chance to see a film more than once. Rerun opportunities were rare in the 1950s, and though there must have been someone who went back on Sunday after a Friday opening, it was never anyone in my family. Why on earth would you want to see a movie that you had already seen? The question would be posed as though no answer were possible; the sheer idea bespoke the indulgence of those, unlike us, with nothing better to do. It never occurred to my parents, or other relatives who took me to the movies, that if they liked a film they might simply—with no tax on their frugality!—remain in their seats and see it again; even when, having arrived late, they were obliged to stay into the second show to see what they’d missed, they would pop up like dolls on a spring at the precise point we had come in.

But their abstemious ethic of “once-and-no-more” may have testified to the very strength of the temptation to linger under the image’s spell. Certainly, what I say didn’t occur to them occurred to me all the time; and, in my desire to prolong the stimulation a movie had given me, I’d often turn back to the screen as I was being taken out of the theater to catch a few second seconds. Being impossible, however, my desire for “a second time” could never have entered that ordinary living room in which I often put a favorite song on the record player, or reread a familiar story; being impossible, it had to be relegated to the psychic subbasement—small, cramped, depressing to visit—where all my more or less shamed quixotisms lay drugged like abducted children. In this captivity, a grandiose desire to win a newspaper contest, or a desperate hankering to be Ronnie Thornton’s best friend, kept company with (the first example I remember) an aching desire to rewatch Pinocchio.

For one of my generation, television might have been an easy means to see movies twice—at least the old Hollywood ones—had not a similar domestic repression prevailed here too, daytime TV being laid under the same embargo as late-night programming. I sometimes attempted to set up a sort of Pleasure Island at my grandmother’s house, where the TV, always on but never watched, was mine to do with as I liked. Planting myself in front of the set, the better to see (already a four-eyes!) and be near the dials, I would sample the forbidden fruit of daytime television: soaps, game shows, Garry Moore, and Hollywood movies from the ’30’s and ’40’s. My truancy was disappointing, not at all like smoking, playing pool, or suddenly sprouting a donkey tail (excitements to come later in life), and the movies on offer (I remember Comrade X and A Midsummer Night’s Dream) bored me fully as much as Queen for a Day and Bert Parks.

But one memorable late afternoon, I found myself watching a movie, a thriller, that grabbed me at the start and held me all the way through. I watched it so raptly that if there had been a thought of seeing it again, that thought was already keeping Ronnie company in the fruit cellar. The next day, at the same time, I returned to the set in the modest hope that I might see something in a similar vein to the film of the day before. What I found was not in the same vein; it was the same film, unfolding on the screen as in the simplest species of dream. And while my eyes were absorbing the visual evidence, my ears took in, during a commercial break, the no less astonishing information that, by the same miracle of programming, I could watch this film again on the following afternoon, which I did, and on every afternoon until the end of my visit to Nonna’s, which I did as well.

I make two observations about this, my first “second time.” The first is that I experienced no difference between my successive afternoon viewings; the breaks between them were as negligible as the commercials within them. I was the same David Albert Miller on Thursday as on Monday, and Dial M for Murder, still trochaically scanning his name, was the same film, shown on the same TV at the same hour; it felt, each time, as if I were simply reentering, with no change, much less diminution, of intensity, a single mystical ecstasy. And the second observation bears on the kind of knowledge I did and didn’t acquire in this paranormal state. Nonna’s mingy black-and-white TV set—not even a console!—would have obscured the film’s structure had I been curious or competent enough to analyze it. But I was not seeking illumination or a film education, only a perpetuation of the enchantment I was under. In any case, far from assisting my understanding of the film, these repeated viewings only succeeded in permanently disabling it, in the way that repeating a mantra empties its words of meaning. In most people’s judgment, Dial M is an ordinary murder mystery, a “thin” Hitchcock, but to me it remains so hypnotic and (probably on that account) so incomprehensible that it might as well be Last Year at Marienbad. If anything, these repeated viewings only tightened the coils of its spell, eliminated any shred of my resistance to it.

Yet as is well known, one does strange things under a spell—performs prodigious feats that one could never achieve, would never attempt, in waking life. Though I understood Dial M no better on Thursday than I had on Monday, by the end of the week, with the memorization skills of youth, but no conscious intention of exercising them, I knew its dialogue by heart. Faute de mieux, I had seized upon the almost unbroken talkiness of the film as an expedient whereby I could reconjure everything else about it as well. This odd source of intimacy, long ago supplemented by a DVD, has not been supplanted. Let a psychiatrist ask me who Margot is, or Tony, or why I am so invested in having her murdered, and him move out of their bedroom; all I know is that, simply by reciting certain lines then learned by heart, I once again go into my old enamored trance. Even as I write this, I hear Tony saying to Swan, with particular aptness to my case: “You used to go to the dog-racing, Mondays and Thursdays; I even took it up myself just to be near you.” That is all my first second time did for me: it got me nearer the love object. But that is all I seemed to want.

Excerpted from Second Time Around: From Art House to DVD, published by Columbia University Press. Copyright 2021. Used with permission.