Return of the Native: Steven Isenberg on teaching in the English Department

In Spring 2015, department alumnus Steven Isenberg taught a Special Topics course titled “Fathers and Sons” in Berkeley. Here is his account of the course and his experience of returning to Cal.

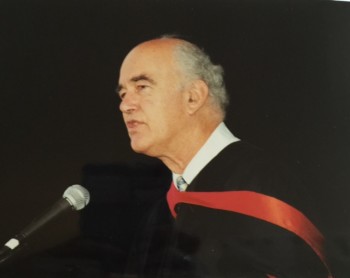

As the speaker at last year’s English Department commencement, I was honored to have my say about my life and times after doing my first degree, majoring in English, here at Berkeley. I believe firmly in the blessings and bounty of a public university (indeed, ours, the greatest) and a liberal arts education. I hope I did my part to bolster confidence in the readiness and adaptability of our graduates.

Having taught a Special Topics course on ‘Fathers and Sons’ this term, I have been asked to write about the return of the native, some fifty-five years since my undergraduate days.

Christopher Ricks, who was my tutor at Oxford (I have kept him in that role ever since I was sent to him by John Searle, who carries on brilliantly in our Philosophy Department, where as a sophomore I was in the first class he taught in 1959), suggested to me a few years ago that I teach a course on fathers and sons. I have done so at the University of Texas at Austin twice as a visiting professor. During my stay at Oxford last fall, as part of a series at my old college, I interviewed two of the authors of memoirs we read here this spring, Alexander Waugh’s (the grandson of Evelyn) Fathers and Sons and Blake Morrison’s And When Did You Last See Your Father. I also gave a talk on Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son, so I was especially primed for my class. Our reading list this term had a good dose of the British, the three just mentioned and J.R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, and Martin Amis’s Experience. We began with Turgenev’s Father and Son. The Americans we read were Philip Roth’s Patrimony, Christopher Buckley’s Losing Mum and Pup, Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life, and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

These memoirs and novels and a play contain the intensity and generational dynamics of the father-son relationship across matters of politics, sex, secrecy, mothers, brothers and sisters, religion, schooling, occupations, favoritism and abandonment, indulgence and neglect, success and failure, as well as rivalry. And, as must be reckoned with, the death and loss of the father. There are fathers who loom and those who shrink. Strengths and frailties, expectations and disappointments, resentments and aspirations, sorrow and humor all play their part, as do the psychological legacies of grandfathers. Lives are lived and are often lived through vicariously. Writers all, their art gives distinctive shape and voices to their recollections and imaginings.

All the books we read and for the most part their authors were unknown to the class. A good deal of what we read was rooted in circumstances and times and idioms far from the experience of our students. (This was also true in the other class I taught in Media Studies, which was called Literary Journalism. Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and Tom Wolfe, as well as contemporaries such as Katherine Boo and Buzz Bissinger, had only slight initial hold there.) The place of British literature in my time seems to hold less sway today for English majors. As we progressed in our readings, the striking power of these works made itself felt. Our class worked to bring their sensibilities and sympathetic understanding to the moment and character of each work, and to see ties that bind. (Again, no less true for the Literary Journalism seminar).

What was remarkable was how deeply so many in our fathers and sons class felt the pull of the emotional situation and larger issues of each book. Some works made their mark more readily; others required more labor and deliberation to grasp. I was most impressed by the maturity and openness of the students in class discussions and in their writing. They saw a connection to dilemmas and tensions that touched deep chords as to their own families and lives. And where the connections were more tenuous they worked hard to imagine themselves into the situation.

In their writing assignments, my assessments of their essays, and in class discussions, we sought to sharpen observations and judgments, and bring them into clear and convincing argument. I said many times over to our group that creating and honing a prose style of clarity and force is a lifetime’s work. I certainly recalled my undergraduate writing and its fault lines of lumpy syntax and overblown diction. I repeated the old newsroom saw: everyone needs an editor. Essays were also an important way I came to know something about what was on the mind of the shy and those who didn’t speak as much in class.

Our class had humor and wisdom . Many spoke their minds and all listened to others with respect. Each student will have certain touchstones from what they read.

I feel many will remember how late in the term we mulled over Waugh’s concluding that ‘..a father’s death resolves nothing. While the son remains the relationship never ends. Neither does it flourish. Instead it trundles round and round on an axis of the mind, suspended, unclosed, incomplete. Most unsatisfactory….Fathers are more important than sons and therein lies the problem.’

And because memory is so much a part of the fabric of this subject – or is it the fabric? – they will not forget Roth’s dream and its admonition: ‘The dream was telling me that, if not in my books or in my life, at least in my dreams I would live perennially as his little son, with the conscience of a little son, just as he would remain alive there not only as my father but as the father, sitting in judgment on whatever I do. You must not forget anything.’

Today’s students are from many more corners, near and far, than those of my time. That is all to the good; Berkeley’s embrace has widened. Of course, my teenage years were in the Fifties; my students’ were in the second decade of this new century. We arrived at Berkeley differently shaped by the schooling, entertainment, economy, technology and world alignments and tensions of our times. But we hold some things in common; as with many of my students, I was the first in my family to go to college and at a tuition rate that would make today’s families weep. For whatever our differences of style and moment, the undergraduates of my day and today share a certain earnestness, restless ambition, energy, a readiness to laugh, the self-consciousness of being young and unfinished, and searching to make their mark. They have great pride in being in and of Berkeley, as did we. And they, too, show a love of literature and of discovering writers and their works,–what lies at the heart of English majors. I am lucky to have had the privilege of teaching here this term to a new generation.